Thomas P. Mackey and Trudi E. Jacobson: metaliteracy is the perfect approach for combating a post-truth world

As outlined by Thomas P. Mackey and Trudi E. Jacobson, the concept of metaliteracy expands the scope of traditional information skills (determine, access, locate, understand, produce, and use information) to include the collaborative production and sharing of information in participatory digital environments (collaborate, produce, and share) prevalent in today's world. Since their first book on the framework, metaliteracy has caught on with librarians and educators far and wide; a second book, spotlighting some of this groundbreaking work, was published in 2016. Mackey and Jacobson's new offering, Metaliterate Learning for the Post-Truth World, goes even further in demonstrating how metaliteracy is a powerful model for preparing learners to be responsible participants in today’s divisive information environment. We spoke with the two editors about the process of putting together this new collection, the metaliterate learner roles, and some suprising applications of metaliteracy in learning environments.

Why did you decide to make this book a collected volume and how did it affect your process of working on this book?

We actually had another book in mind that would have focused exclusively on the “learner as producer” dimension of metaliteracy but given the immediate concerns of the post-truth world, we decided to shift gears and apply metaliteracy to these pressing issues instead. We knew the times required a stronger assertion of metaliteracy to address these challenges from a pedagogical standpoint. The inclusion of additional authors provided the opportunity to expand the scope of metaliteracy theory and practice. Given the complexity of the post-truth concerns, from confirmation bias to false and misleading information, to divisive partisanship, we were interested in working with authors from a range of disciplines who could speak to these issues with positive and effective pedagogical strategies based on the metaliteracy framework.

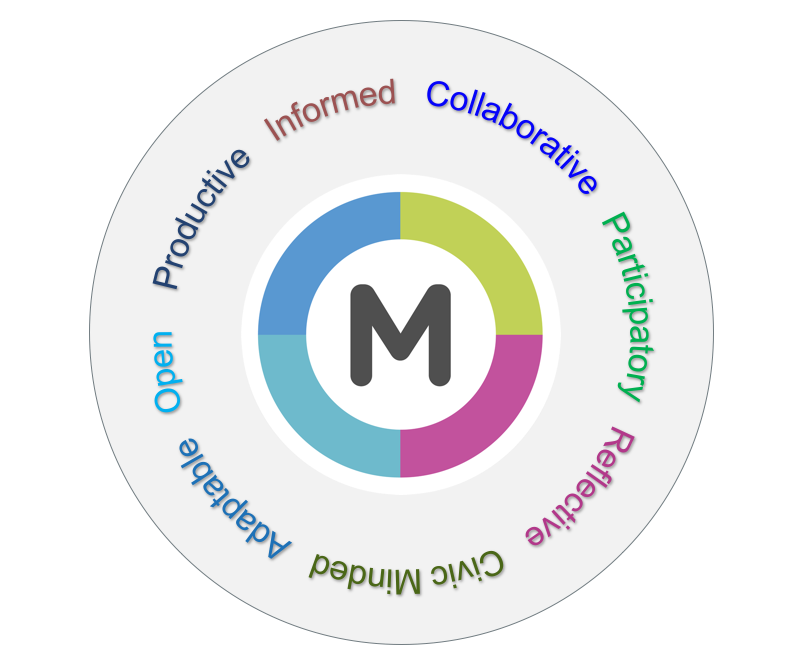

As we planned this new book, we knew that the framing chapter would set the tone and context for all of the chapters based on a new metaliteracy learner characteristics figure we had developed. The first Metaliteracy book presented a transitional figure that illustrated how metaliteracy expanded on information literacy, but now that metaliteracy has matured as a concept, we are able to identify the specific characteristics that define this model as envisioned today. We also knew that we wanted to revise the Metaliteracy Goals and Learning Objectives in response to the challenges of the post-truth world, so we did that as the framing chapter was being written and incorporated that work into the first chapter. We shared drafts of the revised metaliteracy goals and learning objectives with chapter authors who also addressed the revisions in their chapters. The edited format of this book is one of the strengths of the volume, and we are so appreciative of our authors for the innovative contributions they have made to the continued development of metaliteracy. Troy Swanson's exceptional Foreword provides a larger context for this work in the field of information literacy and in higher education more broadly.

We are so proud of this book and the work of our chapter authors who apply metaliteracy to their research and teaching while expanding the framework in new and exciting ways.

This is your third book on metaliteracy. Why do you think this concept continues to connect with librarians and other educators so strongly?

Librarians and other educators, including disciplinary faculty, understand the enormous responsibility that comes with being a participant in our current information environment. This involves not only a responsibility on the part of an individual, but the concomitant implications for society as a  whole. The emphasis that metaliteracy places on metacognition is critical for being a responsible metaliterate citizen. Metacognition supports reflective thinking and self regulation so that individuals are capable of evaluating their understanding of information to determine if it is accurate and valuable within the information environments they engage in. This informs the sharing or re-use of such information, and the production of new information-based creations, either individually or collaboratively. This may seem admonitory, but there is also enormous potential in envisaging or recognizing oneself in these expansive metaliterate learner roles. Librarians and other educators have the opportunity to introduce metaliteracy to the students they work with, and to enhance how they think about their roles in the information environment.

whole. The emphasis that metaliteracy places on metacognition is critical for being a responsible metaliterate citizen. Metacognition supports reflective thinking and self regulation so that individuals are capable of evaluating their understanding of information to determine if it is accurate and valuable within the information environments they engage in. This informs the sharing or re-use of such information, and the production of new information-based creations, either individually or collaboratively. This may seem admonitory, but there is also enormous potential in envisaging or recognizing oneself in these expansive metaliterate learner roles. Librarians and other educators have the opportunity to introduce metaliteracy to the students they work with, and to enhance how they think about their roles in the information environment.

In our own teaching and learning collaborations we have found that the idea of metaliteracy in practice resonates with faculty and librarians. We have developed learning objects and learning activities in our MOOC projects and Metaliteracy Digital Badging system that have had wide appeal at our institutions and beyond. The MOOC content is openly available for instructors and learners to use and our digital badging system support faculty and librarian collaborations within specific course contexts. The books provide the theoretical grounding and praxis and the associated projects developed by the Metaliteracy Learning Collaborative have provided extensive learning resources and in many ways have modeled how metaliteracy can be applied in a range of pedagogical settings.

Would you talk about the extensions to metaliteracy as found in the first section of the book?

In addition to the framing chapter, which provides the most current analysis of metaliterate learner characteristics, along with the revised metaliteracy goals and learning objectives, the first part of the book also includes chapters that apply metaliteracy to documentation theory, inoculation theory, scientific literacy, and the synergistic relationship of word and image in photojournalism. Each of these chapters builds on the metaliteracy framework and moves the theoretical understanding of the model into new and exciting areas. All of the chapters in this section offer innovative explorations about how metaliteracy is applied in different disciplinary contexts and demonstrates the value of including colleague authors in the book to discuss strategic pedagogical responses to the post-truth world. In his chapter, “When Stories and Pictures Lie Together—and You Do Not Even Know It” by Thomas Palmer, for example, the author provides several striking examples of how visual information is easily manipulated online to convey meanings and interpretations never intended in the original imagery. Tom Palmer’s perspective as an educator in the Department of Journalism at the University at Albany, and Editorial Design Director/News Editor at the Times Union newspaper in Albany, New York provides critical insights about the importance of professional journalism, and the need for exceptionally high standards during a time when the field is under attack. Each author shows how metaliteracy, as an evolving and collaborative concept, benefits from multiple perspectives.

You write in your preface, “There is a particular urgency in publishing this book now, when truth itself has been questioned by partisan leaders for political purposes, professional journalism is under attack, science and climate change are doubted as factual, online hacking is prevalent, and personal privacy has been violated by commercial and political interests.” What are some ways that metaliteracy can serve as a tool for separating truth from fiction?

Excellent question and this is why you need to read the book! In short, metaliteracy provides a pedagogical perspective that encourages reflective thinking and promotes active metaliterate roles such as producer, communicator, researcher and even teacher. We argue that in today’s highly connected yet divided information environment, we all need to be informed consumers of information who actively evaluate the authenticity of digital and social information we engage with on a daily basis. This requires critical thinking and source verification but there is more involved because the professional looking texts and images we encounter through social technologies can be misleading and inaccurate in content and form. In addition, today’s information environment includes untruthful information that is intentionally produced and shared from sources once considered at least official or professional, but now the same office or institution may be the actual source of false and misleading information. Metaliteracy emphasizes the need for checking bias in all forms of content, and in oneself, as a continuous reflective process. Metaliterate learners take charge of their own literacy and learning by identifying strengths as well as gaps in knowledge, to make decisions about where to take one’s educational journey. Since metaliteracy supports learners in active roles such as producer and communicator, the responsibilities that are part of creating something of value, and then sharing it with a broader audience, are also reinforced through this model. In collaborative environments, the metaliterate learner is also teacher because an individual’s knowledge is co-created and shared with others. This requires an understanding of the ethics of social information, emphasizing the need to critically evaluate content that is consumed, produced, and distributed.

Among the examples of praxis and case studies in the second half of the book, what’s an application of metaliteracy that surprised you or that you found unexpected?

We were pleased to see a range of fields represented by the case studies--theater, literature, information literacy, and library and information science. And we were particularly delighted that two of the authors in this section had attended a metaliteracy workshop that we presented at Temple University--to see the impact that metaliteracy had on their courses is very exciting. Kimmika Williams-Witherspoon is one of those authors. She is Associate Professor of Urban Theater and Community Engagement at Temple, and her use of the metaliteracy framework was in her Urban Ethnography course. Her students learn “how to develop ethnographic and personal narratives set to poetry about Philadelphia neighborhoods and their people,” which helps to give the voiceless a voice. The application in this course is notable not only for being in the performing arts, but also for the community engagement aspect.

How might educators in the field of LIS and beyond apply metaliteracy to the post-truth issues examined in your new book?

LIS professionals might keep in mind the metaliterate learner roles and the powerful impact that metacognition has when teaching students or working with patrons. They might challenge learners to reflect upon their roles and responsibilities in connection with information, and also to consider how they might expand their conceptions of themselves in this regard. Those who work with faculty have the opportunity to introduce them to the concept of metaliteracy. We recently wrote a piece for HigherEdJobs, "Why You Should Fight for Metaliteracy on Your Campus," that speaks to all  educators and administrators. Sharing this piece, or information from it, would be a good way to initiate a conversation. LIS professionals who work with the ACRL Information Literacy Framework for Higher Education, which was influenced by metaliteracy, may explore deeper links between the two.

educators and administrators. Sharing this piece, or information from it, would be a good way to initiate a conversation. LIS professionals who work with the ACRL Information Literacy Framework for Higher Education, which was influenced by metaliteracy, may explore deeper links between the two.

As Troy Swanson notes in his Foreword to the book, many of the chapter authors are outside of the field of LIS, demonstrating the interest in metaliteracy beyond this profession as well. The ideas explored in this book are definitely applicable within LIS and could also be applied in general education courses, multiple disciplinary contexts, and even K-12 and graduate education. We know there is a lot of interest in how to deal with the challenges of the post-truth world and this expanded interest in metaliteracy will support LIS collaborations at many different institutions. This is really everyone’s concern, and developing effective pedagogical strategies that support reflective thinking and empowered metaliterate learning roles in participatory environments will prepare learners for ethical participation in communities of trust. Educators and learners are looking for resources for doing so and this book, along with the learning activities and learning objects we have been developing, based on the metaliteracy learning goals and objectives, provide a starting point for the adaptation of these ideas in many different contexts.

As we finished the book we applied for and were then awarded an Innovative Instruction Technology Grant (IITG) supported by the State University of New York (SUNY) to develop a new Open EdX MOOC Empowering Yourself in a Post-Truth World. This course builds on our previous MOOC and digital badging projects with a particular emphasis on applying metaliteracy to the challenges of the post-truth world. It aligns nicely with the book and will allow us to put many of the strategies into practice. This new openly available metaliteracy MOOC will launch in March 2019. For all of our most recent updates be sure to follow Metaliteracy.org!

Learn more at the ALA Store.