Interview: Patricia C. Franks surveys the RIM landscape

As a writer and teacher, Patricia C. Franks has the great gift of making complicated and often abstract concepts like "information" and "records" easy to grasp. So it's no wonder that her book Records and Information Management was an immediate bestseller, a hit with both students and practitioners. Now, after several years of work, the revised and updated second edition has just been published and promises to be every bit as successful. We had the chance to speak with Franks about tackling this new edition, how the field has changed in the last five years, and her advice for mastering the basics.

The reaction to the first edition was overwhelmingly positive, with many reviews predicting that your book was poised to become the go-to text for RIM students and professionals. Was it daunting to start on the second edition? Was your approach different this time around?

It was gratifying to learn that the first edition had received positive reviews from students, faculty, and RIM professionals. However, for that reason it was somewhat intimidating to attempt to produce a second edition. Fortunately, the first edition provides a solid foundation upon which to build, and the feedback from many individuals, including the members of the editorial advisory board, helped me formulate an approach to the revision. This involved removing outdated information and references, expanding upon concepts that deserved additional attention, and introducing new ideas (e.g., Information Economics) and emerging technologies (e.g., Internet of Things platform and Blockchain Technologies) while continuing to address our responsibilities to care for physical records that possess intrinsic value, such as the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath—the original record from the kingdom of Scotland to Pope John XXII. These changes required the addition of two additional chapters: “Long-term Preservation and Trusted Digital Repositories” and “Information Economics, Privacy, and Security.”

In addition, additional resources are being made available with the second edition. The paradigms (case studies) or perspectives (thought pieces) written by guest authors that concluded each of the 12 chapters in the original book were moved to a separate publication, available to course instructors  at no charge. New paradigms or perspectives now complement each of the 14 chapters of the second edition. And, for the first time, from two to three slide decks were created to accompany each chapter and are available to educators who use the new edition for their classes. [Ed. note: contact us for more information.]

at no charge. New paradigms or perspectives now complement each of the 14 chapters of the second edition. And, for the first time, from two to three slide decks were created to accompany each chapter and are available to educators who use the new edition for their classes. [Ed. note: contact us for more information.]

What are some of the biggest changes in the records/information landscape over the last five years?

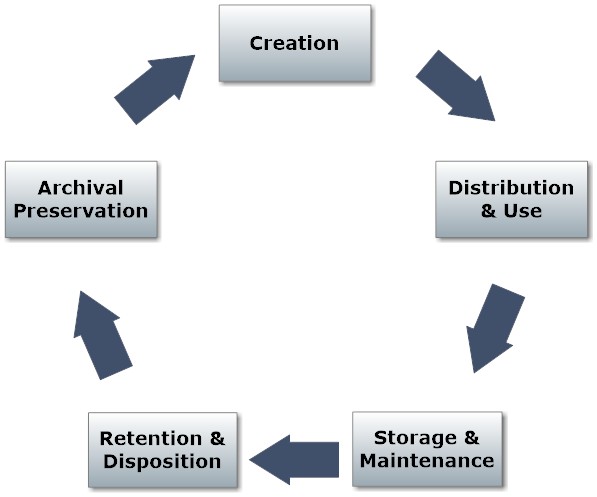

Although our profession is constantly evolving in response to technological, cultural, legal, and social trends, much of the change in the past five years can be attributed to the increased volume and variety of records and information created and the velocity at which this occurs. This change has had an impact on the methods used for capture, management, storage, use, preservation and disposition. Artificial Intelligence (AI), the growth in the use of mobile devices, social engagement technologies, and the Internet of Things (IoT) are just some of the technological advances driving data complexity, new forms and sources of data. Take, for example, the Internet of Things—the network of physical devices, vehicles, home appliances, and other items embedded with electronics, software, sensors, actuators, and connectivity—which enables devices to connect and exchange data. How do we govern this data, assess and mitigate risk, and ensure compliance with laws and regulations?

The very definition of what constitutes a “record” continues to evolve. What’s your simplified definition?

The definition of a “record” I recommend to readers is the one presented in the records management standard, ISO 15489-1:2016, Information and documentation—Records management—Part 1: Concepts and Principles: “information created, received and maintained as evidence and as an asset by an organization or person, in pursuit of legal obligations or in the transaction of business." The terms “evidence” and “asset” are significant. The term “evidence” does not imply that the information will be used in a court of law, although it may be. Rather presents “proof” that an event has taken place and takes form as a “representation” of that event, such as an agreement made by two parties to transfer ownership of property represented by a signed and dated contract. The term “asset” implies the information (including those considered records) has value to the organization, not merely as evidence that something has occurred but as data that can be leveraged to enable the organization to reach its business goals. This notion, information as intangible assets, is the basis for a new chapter in the second edition of this book, Chapter 10—"Information Economics, Privacy and Security."

What advice would you give students who may feel intimidated by the sheer breadth of what constitutes records management?

My advice is to first “master the basics” and then to “understand the big picture.” While it is important to be aware of the latest trends that impact records management, students should first become familiar with records management theories, principles, and practices that grew out of the real-world struggles of others to manage records—start with the basics. Next, students should understand that records and information management is only one of several functions that exist to support the organization in its business operations—understand the big picture. How can records management be aligned with business and information systems, information governance and risk management? How can it add value to the organization? These two topics are addressed in Chapters 1 and 2 of the text: “The Origins and Development of Records and Information Management” and “Building an Information Governance Program on a Solid RIM Foundation. It’s only after students master the basics and understand the big picture that they are ready to explore the operational issues related to managing records and information in their many forms.

In your opinion, what are the greatest preservation challenges presented by digital records? What pointers can you offer RIM professionals for keeping up to date with the latest developments?

Digital records face numerous preservation challenges, which are magnified as the volume of digital data created increases. These include determining what should be preserved, in which file formats, and whether laws or regulations restrict access such as U.S. Copyright laws or the E.U.’s General  Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Other challenges relate to file formats and storage media. We know that media used for storage—such as hard drives, tapes, and CDs—fail. We also know that file formats quickly become obsolete. The solution to these challenges may be investment in a trusted digital repository to preserve content, migrate it to new file formats, and provide access to in-house users and, if appropriate, the public. Determining the best solution involves two additional considerations—funding and human resources. I advise reading articles in both academic and trade journals and attending trade-shows to view demonstrations of the products and ask questions of vendors. However, there is no substitute for learning from those who have implemented trusted digital repositories. Two examples presented in Chapter 12 of the text explain the steps taken to arrive at two very different solutions to the challenges presented to digital preservation of records: “Use Case—eArchive for Pharmaceutical Pre-Clinical Research Study Information” and “Archivematica to ArchivesDirect: A Practical Solution for Limited Staff Resources.”

Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Other challenges relate to file formats and storage media. We know that media used for storage—such as hard drives, tapes, and CDs—fail. We also know that file formats quickly become obsolete. The solution to these challenges may be investment in a trusted digital repository to preserve content, migrate it to new file formats, and provide access to in-house users and, if appropriate, the public. Determining the best solution involves two additional considerations—funding and human resources. I advise reading articles in both academic and trade journals and attending trade-shows to view demonstrations of the products and ask questions of vendors. However, there is no substitute for learning from those who have implemented trusted digital repositories. Two examples presented in Chapter 12 of the text explain the steps taken to arrive at two very different solutions to the challenges presented to digital preservation of records: “Use Case—eArchive for Pharmaceutical Pre-Clinical Research Study Information” and “Archivematica to ArchivesDirect: A Practical Solution for Limited Staff Resources.”

Learn more at the ALA Store.