Building literacy skills through creative writing: a conversation with AnnMarie Hurtado

Decades of research show that children learn to read through writing. Creative writing in particular encourages children's'imaginations to take flight. In this way, a form of play can also build literacy skills. First-time author AnnMarie Hurtado explains this approach in her new book 36 Workshops to Get Kids Writing: From Aliens to Zebras.

So ... your first book! Congrats! What was it like? And what did you find the hardest about the process? How did you stay motivated?

I really loved working with ALA Editions. I would love to write for you again. Jamie Santoro was my acquiring editor and she was a gem, offering a lot of feedback and support throughout the writing. And my hats off to Angela Gwizdala, who has been taking the draft and all my ideas for the handouts, and working with the designers to make everything come together!

I submitted a proposal to ALA Editions in late 2016, and after my proposal for the book was accepted, I dove into the research. I wanted to know all about how creative writing impacts children's development of reading fluency and overall academic success. The things I learned for the writing of this book have continued to benefit my work at the library to this day. I have tried as often as possible to share those insights with parents who come to the library. I think that's what kept me motivated, to tell the truth; the feeling that this book needed to be written. The more I read about how reading and writing go hand in hand, the more I sensed I was hitting on something librarians are not told enough in library school. We don't get a lot of training on how people learn to read, but teachers do, and through organizations like the National Council of Teachers of English I was able to tap into an ocean of materials going back to the 1980s on the connection between reading and writing.

Research was a lot of fun, and it was all-consuming for about two months. I had numerous ILLs and lengthy visits to Pasadena City College Shatford Library. I would say that knowing how to do research and find current and historical information on a topic is a great skill for any writer, and that if you're a librarian who has considered making the leap into writing and publishing, you should know you already have a strong skill set that will help you, not to mention a supportive community of fellow librarians (like the librarian who helped me at PCC).

The hardest part was probably switching from research mode to writer mode. Jamie often counseled me that the research was great, but I needed to also find my own voice and convey my own insights. Her help was invaluable. I worked hard on it in whatever snatches of time I could find at home, on weekends, in coffee houses, in libraries, and in the break room on my lunch breaks at work. The bulk of the writing took about six months. Having a detailed proposal at the start ensured that I never had writer's block. It just wasn't always easy finding time (because I have two small children at home). Fortunately I had supportive family who were able to lend a hand now and then.

How did your work at the Pasadena (California) Public Library inspire this book?

When I started working in the Youth Services department of the Pasadena Central Library five years ago as a children's librarian, I was putting on writing workshops for tweens using prompts inspired by good middle grade books. Having a young daughter of my own I started to notice a gap in the programs libraries provide to kids as they age out of traditional preschool programs and yet are too young for advanced tween programs like some of the STEAM programs I did or the writing workshops. In many ways children in kindergarten and 1st grade are also a little too young for traditional book clubs or book discussions. The primary grades are difficult to reach because kids are becoming independent readers and writers, and yet the books they are interested in are too hard to read. Instead, craft programs tend to be the afterschool program of choice for public libraries wishing to offer something to early elementary school kids, and it's not hard to see why - it gives them fine motor skill development while also giving them range to learn and express their creativity.

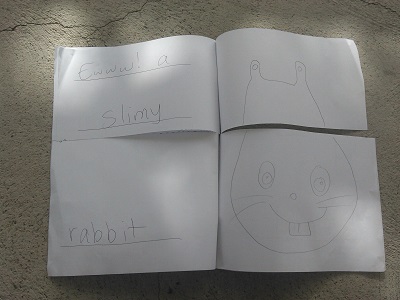

But when their older siblings were signing up for our tween creative writing workshops, many younger kids and their parents were disappointed that they were considered too young to write stories. They knew what I would soon learn - that they were old enough to make up stories of their own. I realized I needed to develop something that would be more catered to the primary grade student's growing abilities. I started a creative writing program just for kids 5-8 years old. I'd choose a picture book, print out clip art and coloring pages, and spread the printed images all over the tables, along with scissors, glue, crayon and markers. I bought blank books for kids to make their own stories, which they illustrated with those glued-in clip art printouts. Having the images sometimes helped kids to come up with something fun to write about. It was almost like a craft program about making your own book.

But when their older siblings were signing up for our tween creative writing workshops, many younger kids and their parents were disappointed that they were considered too young to write stories. They knew what I would soon learn - that they were old enough to make up stories of their own. I realized I needed to develop something that would be more catered to the primary grade student's growing abilities. I started a creative writing program just for kids 5-8 years old. I'd choose a picture book, print out clip art and coloring pages, and spread the printed images all over the tables, along with scissors, glue, crayon and markers. I bought blank books for kids to make their own stories, which they illustrated with those glued-in clip art printouts. Having the images sometimes helped kids to come up with something fun to write about. It was almost like a craft program about making your own book.

I saw kids who hardly spoke a word of English at our first meeting come every month to draw, cut and paste, and write a few words, and within six months they were writing their own funny sentences in English, inspired by the books we read. I saw boys and girls collaborate on exciting pirate stories the same way I did when I was a kid playing with my sisters. And it struck me that this sort of creative writing program was something that other libraries could benefit from, replicate, and modify, to reach our goal of promoting literacy - Talking, Singing, Playing, Reading, and WRITING.

Yes: one mantra you repeat throughout the book is that children learn to read by writing. At what age do you get kids started? And as librarians and educators, *how* do we start?

I'll include parents in this as well: as soon as your child can hold a pencil or crayon, start asking them to tell you what they are drawing and helping them to write it down. Ask the child to tell you stories and write the stories down for them. Model writing for them - be an adult who writes and who models for your child how valuable it can be to be able to express something important by scrawling symbols on paper. Then encourage them to write down their own stories and letters without help (these stories will look like illegible scribbles at first). Ask them to read the stories to you. And of course, read, read, read to them often.

One of the researchers and authors whose work was immensely important to me as I was researching this book was Lucy McCormick Calkins, who wrote about how reading and writing develop hand in hand, around the same time in a child's life. Invented spellings, for example, (writing "pupe" to indicate a puppy) is an important step in the learning process for the development of decoding skills. Just as crawling precedes walking and babbling precedes talking, scribbling and invented spellings indicate a person who is well on their way to becoming truly literate. We can talk about the phonetics of the words but it is very important that we not discourage kids. We are here to help them to appreciate books and add their own ideas to the world of literature, and through that engagement they will develop their ability to read and write, to construct meaning. Kids have to feel that their early efforts at writing are meaningful and fun, just as babies need to feel that their early attempts at communication are giving them connection with their parents. You don't understand everything your five-month-old is saying, but by pretending you do, you show them that you are listening and you care. Do the same thing with your five-year-old's writing. That connection is what's most important for the young child; refinements such as standard spelling will come with practice.

I'm sure some children's librarians are thinking, gee, kids can get really rambunctious! So when you're doing a storytime, how do you channel that energy productively into creative writing activities?

It's certainly a challenge, yes! I recommend involving the kids in a group writing activity or a group brainstorming activity, and letting it be as long and as energetic as possible. Spend at least ten minutes on the group writing (and if you can spend longer that's great!). Get their ideas flowing. Ask the kids lots of questions. Let them be the experts and you the scribe. Get your pen flying all over the whiteboard to capture their suggestions. If you are enthusiastic and focused, you will help to ignite and focus the children's enthusiasm. And after they have been focused on the group writing activity for at least ten minutes, they'll be ready to do some individual writing. The room will not likely be a quiet one - kids will be talking, sharing their ideas, asking you questions. My workshops are usually very noisy, but vibrant!

I also recommend making the writing activity as "crafty" as possible for the kids. Give them supplies to color, cut, glue. Break out the glitter now and then. Kids need to have a variety of activities available, and they need a wide range of artistic expression when illustrating their stories.

When working with older children, how do you vary the approach?

Older kids don't need quite so many different segments or activities in their workshops - they can focus on writing for a longer time, and they rarely need to do illustrations. But I think the really surprising thing is how much of the approach is actually the same for older kids. Instead of cute blank books I give them legal pads, but many of the writing prompts I give them are similar to what I'd give the younger kids. That might be because I never like to underestimate what younger kids can do.

Older kids don't need quite as much help or scaffolding when it comes to generating their stories or writing things down, but the use of a mentor text to center our discussion on the writer's craft is essentially the same approach with both groups. I always read excerpts from stories at the very beginning - usually from a middle grade novel, but not always. A picture book can be a surprisingly effective mentor text for teaching older kids advanced concepts about writing, such as plot. It's hard to break down the plot of a novel in a fifteen-minute discussion, but it's not so hard with a picture book. So several of the picture-book-based writing workshops in my book will actually work quite well even with older kids. For example, one of my workshops uses the picture book Giraffes Can't Dance by Giles Andrae as the center of a lesson on The Hero's Journey. Once they make the connection to their favorite hero stories from other books and movies, older kids are generally able to learn the steps and then get to work crafting their own epic plots. I've also used the poetry workshops from this book with older kids, and they loved it.

Older kids don't need quite as much help or scaffolding when it comes to generating their stories or writing things down, but the use of a mentor text to center our discussion on the writer's craft is essentially the same approach with both groups. I always read excerpts from stories at the very beginning - usually from a middle grade novel, but not always. A picture book can be a surprisingly effective mentor text for teaching older kids advanced concepts about writing, such as plot. It's hard to break down the plot of a novel in a fifteen-minute discussion, but it's not so hard with a picture book. So several of the picture-book-based writing workshops in my book will actually work quite well even with older kids. For example, one of my workshops uses the picture book Giraffes Can't Dance by Giles Andrae as the center of a lesson on The Hero's Journey. Once they make the connection to their favorite hero stories from other books and movies, older kids are generally able to learn the steps and then get to work crafting their own epic plots. I've also used the poetry workshops from this book with older kids, and they loved it.

I have an adult friend who has special needs, and every other week we get together to do some creative writing. It gives her practice with her reading and writing skills so that someday she can get her GED. Sometimes I use workshops from this book. She and I are currently writing a very funny story about her and her dog getting in a time machine and ending up on a medieval battlefield. We read books about knights for research and inspiration, and then we take turns writing alternate sentences of the story. It's an approach I've used with kids that seems to be surprisingly effective with my adult friend. Perhaps approaches don't have to vary quite so much by age or grade level - perhaps at our core, we're all creative beings who enjoy stretching our imaginations to write something funny and weird and nonsensical every now and then.

Lastly, one chapter in your book is titled "All You Need Is a TERRIBLE Idea" ... what's the idea behind that?

As I was compiling my list of picture books and ideas for writing prompts for my book proposal, I noticed something - many of the really funny picture books I love are about characters doing something silly or foolish, or putting two things together that normally aren't. And it just started to make sense to me: all you need for a good story is a really terrible idea. Books like that were easy to create writing activities for, because they work on an imaginative sort of logic that prompts multitudes of possibilities. But I also noticed that those silly picture books are intrinsically appealing to kids, and that if you give a kid a book about something that makes no sense, they will be curious to see what happens and will anticipate laughs and fun along the way. Furthermore, if you give a kid a writing prompt that is rooted in nonsense, you free the kid's imagination to do anything they like with that premise - imagining a parade of snails, for example, or trying to teach an alien how to use the toilet. In the end, the child writer bring herself and her ideas to it, and pretty soon she is creating something she never would have dreamed she'd be creating.

Now, some teachers will prefer to encourage kids to just write about themselves and their experiences, and there is definitely a place for that. But when you have a group of kids who don't know each other, as we usually do at the public library, you have to tickle their funny bones. It's the quickest way to their creativity!

Read an excerpt from the book at the ALA Store.